Till the establishment of an independent Singapore in 1965, the legal system of Singapore was intricately linked with its British colonial master. This was followed even after independence, by Singapore following the common law system. Singapore has shifted towards developing an autochthonous legal system. The guiding principle is that the adoption of any legal practice or norm must be compatible with Singapore’s cultural, social and economic requirements.

Features of Legal system of Singapore

Constitutional framework

Singapore is a republic while having its own written constitution which acts as the supreme law of the land. It acts as a guideline for the fundamental rights of the citizens in part IV of the constitution and establishes a government which is divided into three branches: the Executive (led by the President and the Cabinet), the Legislature (Parliament), and the Judiciary. The amendment procedure for the provisions of the Constitution includes both, voting by a two third majority by the members of parliament, and sometimes through a national referendum before amendments can be made. The constitution also grants general protection to racial and religious minorities while granting a special position to Malayas.

Common law system

Singapore’s legal system has its roots in English common law, where past court rulings (precedents) help guide decisions. Over time, Singapore has tailored this system to fit its own societal and legal needs, making it unique compared to other common law countries. Judges prioritize statutory law laws passed by the government but when such laws are absent, they turn to previous court decisions for guidance. This flexibility allows the system to evolve while maintaining order and consistency.

The Judiciary

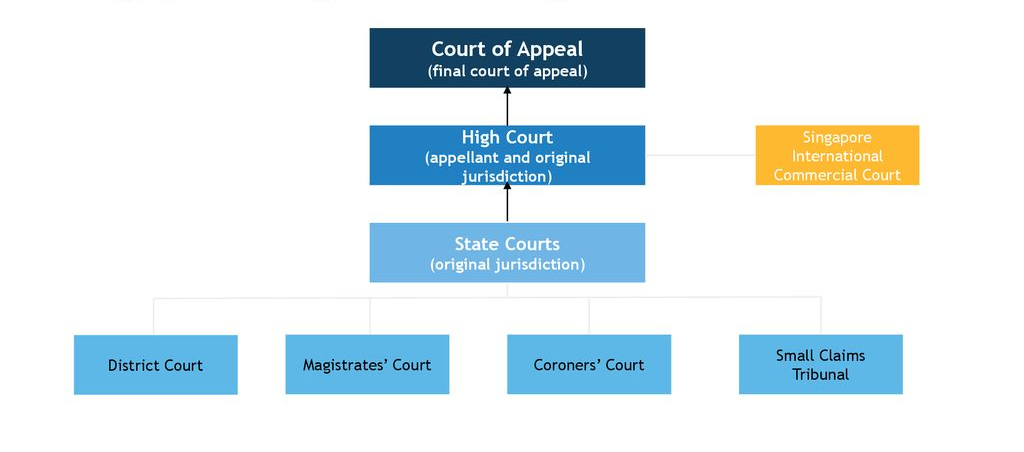

Singapore’s judiciary is respected for its independence and strong ethical standards. It has two main levels: the Supreme Court and the State Courts. The Supreme Court consists of the Court of Appeal, which is the highest authority, and the High Court, which handles serious cases. The State Courts manage less complex matters. Together, they work to ensure justice is served, maintaining the rule of law and fairness in the legal process, making Singapore’s legal system efficient and trustworthy.

Legislation and Legal development

Parliament in Singapore plays a key role in creating and updating the country’s laws. While many of these laws originated during British colonial times, they have been carefully adapted to suit Singapore’s own culture, values, and current needs. Parliament regularly reviews the legal framework to ensure the laws stay relevant, keeping pace with both local changes and global standards. This constant refinement helps Singapore maintain a modern, responsive legal system that meets the demands of its people and the international community.

The judicial system of Singapore

Singapore’s judiciary is well respected worldwide for its efficiency and innovative reforms. Since Chief Justice Sundaresh Menon began his tenure in 2012, the system has seen significant enhancements, including the establishment of the Singapore International Commercial Court, which reinforces the country’s status as a premier hub for international commercial dispute resolution.

The judiciary consists of the Supreme Court comprising the Court of Appeal and the High Court and the State Courts. Judges are tasked with both interpreting laws and determining facts, especially after the jury system was abolished in 1970. The introduction of Family Justice Courts emphasizes a non adversarial approach to family disputes. Additionally, Senior Judges, who are retired judges, lend their experience to help manage workloads and mentor junior judges.

In 2015, the Centre for Dispute Resolution was created at the State Courts to consolidate alternative dispute resolution services, improving the judiciary’s ability to resolve conflicts efficiently without resorting to lengthy trials.

Hierarchy of courts in Singapore

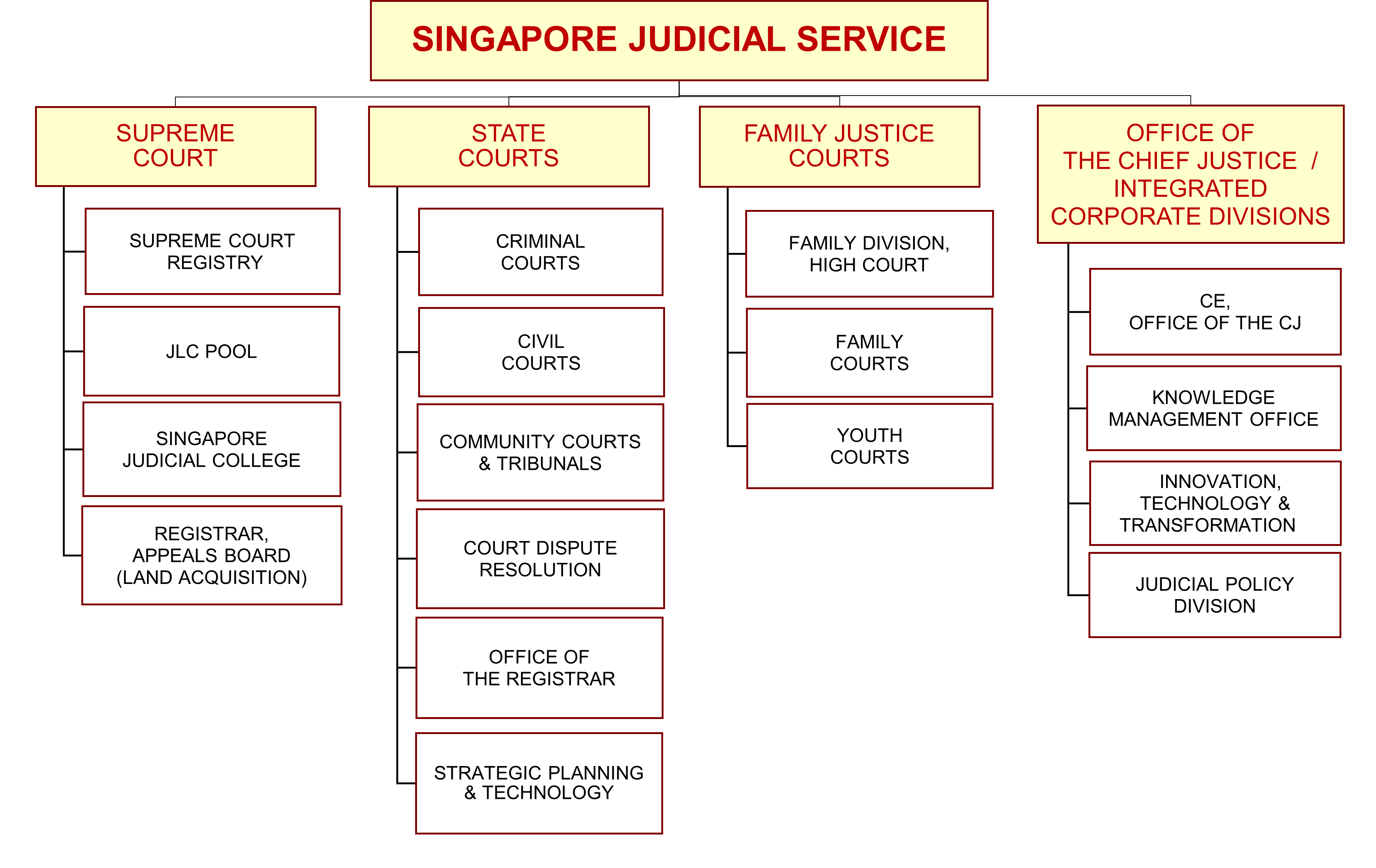

The Singapore judiciary consists of three distinct branches, namely the Supreme Court, the State courts and the Family Justice court. The supreme court consists of the High court and the court of Appeals, while the high court is further divided in the General division, the Appellate division and the Singapore International Criminal Court.

On the other hand, the State courts consist of several courts and tribunals including the District Court, the Magistrate’s Court, the Coroner’s Court, the Small Claims Tribunal, the Community Disputes Resolution Tribunal, the Employment Claims Tribunal and the Protection from Harassment Court.

Lastly, the Family Justice Courts consist of the Family Court, the Youth Court and the Family Division of the High Court.

The Supreme Court

A. Court of Appeals: It is the apex court of Singapore hearing all the criminal appeals against decisions made by the General Division in the exercise of its original criminal jurisdiction. While it deals with the appeals of every criminal matter, it has jurisdiction over only limited civil appeals, including appeals arising from a case related to constitutional law, administrative law, law of arbitration and appeals arising from a case relating to insolvency.

B. Appellate division of the High Court: It hears civil appeals that are otherwise not allocated to the Court of Appeal. It does not have any criminal jurisdiction and does not hear criminal appeals.

C. General Division of High Court: hears both civil cases where the value of the claim exceeds $250,000, and criminal cases where the offense is punishable with death or an imprisonment term exceeding 10 years. The issues heard here also include admiralty matters, insolvency and bankruptcy matters and appeals from tribunals and criminal and civil appeals from the state courts.

D. Singapore International Commercial Court (SICC): It hears international commercial disputes such as claims that are international and commercial in nature and cases related to international commercial arbitrations.

State Courts

A. District Courts: It hears both criminal and civil cases. It hears criminal cases where the maximum imprisonment term does not exceed 10 years, or which are punishable with a fine only. It hears civil claims of more than $60,000 and up to $250,000

B. Magistrate’s Court: It hears both criminal and civil cases. It hears criminal cases where the maximum imprisonment term does not exceed 5 years, or which are punishable with a fine only. It hears civil claims not exceeding $60,000 in value.

C. Coroner’s court: It conducts inquiries into sudden or unnatural deaths or where the cause of death is unknown.

D. Small Claims Tribunal: It hears claims not exceeding $20,000 in value for certain disputes. They include disputes arising from a contract for the sale of goods or provision of services, disputes arising from a tort in respect of damage caused to property and disputes arising out of residential leases not exceeding 2 years

E. Community dispute resolution tribunal: It hears claims not exceeding $20,000 in value arising out of disputes between neighbors involving unreasonable interferences with the enjoyment or use of places of residence.

F. Employment claims tribunal: It hears claims not exceeding $20,000 in value arising out of disputes between employers and employees involving salary or wrongful dismissal.

G. Protection from harassment court: It hears cases specified in the Protection from Harassment Act, such as seeking protection orders against behavior causing harassment, alarm or distress or against unlawful stalking.

Family Justice Courts

A. Family Courts: It hears all family-related cases, including divorce, probate and administration, maintenance, protection against family violence, deputyship, adoption, protection for vulnerable adults, guardianship and international child abduction.

B. Youth Courts: It hears cases under the Children and Young Persons Act, including cases relating to family guidance, care and protection and youth arrest (namely criminal cases involving youth offenders).

C. Family division of the High Court: It hears family proceedings involving assets of more than $5 million, probate matters where the value of the deceased’s estate is more than $5 million, appeals against decisions of the Family Court or Youth Court and cases involving important questions of law or test cases.

The Singapore Bar Association AKA Law society of Singapore

The society provides services and support to lawyers in Singapore, does advocacy for issues affecting its members, publishes the Law Gazette, and operates a pro bono scheme to provide access to justice for those who may not be able to afford it. The society’s motto is “An Advocate for the Profession, An Advocate for the Community.” The society has various standing committees tasked with managing particular issues or areas of practice, including an advocacy committee, alternative dispute resolution committee, civil practice committee, information technology committee, amongst others.

A person must acquire the stats of a qualified person to be admitted to the Singapore Bar. For this, you need a law degree from recognized institutions such as the National University of Singapore (NUS), Singapore Management University (SMU), Singapore University of Social Sciences (SUSS), or approved overseas universities in the UK, US, Australia,, and New Zealand.

Graduates of authorized international universities are required to complete Part A of the Bar Examination, which is a Singapore law conversion course. Graduates from SMU and NUS, however, are not subject to this requirement. All graduates, domestic and international, must successfully complete the Preparatory Course leading to Part B of the Bar Examinations and fulfill a six-month training program as a Legal Service officer or in a Singaporean legal firm.

Graduates from accredited institutions may be accepted as Advocates and Solicitors starting in 2023, provided they pass the Part B examinations. However, they can only begin practicing law following the completion of a 12 month training contract.

Foreign attorneys who meet the requirements can apply for a Foreign Practitioner Certificate, which allows them to practice in certain areas of Singaporean law, including intellectual property and banking. If local experience is insufficient, Queen’s Counsel from the UK may also be invited on an as needed basis for complicated matters.

Comparison between the Indian and Singapore legal system

Due to their common law roots and their colonial pasts under British control, Singapore and India both have legal systems that are based on similar fundamental principles. This indicates that the laws of both countries are significantly shaped by court precedents. Both nations also have written constitutions, with Singapore’s being far shorter than India’s and India’s being among the longest in the world. Both systems place a strong emphasis on judicial independence, guaranteeing that courts may provide judgments free from intervention from the executive or legislative departments. Both nations also have a judicial system that is hierarchical, with lower courts handling regular matters and higher courts serving as appellate tribunals.

But there are some significant variations. Singapore’s legal system is more simplified and predominantly influenced by English law with local adaptations, but India’s legal system is more complicated due to its combination of colonial law, religious traditions, and customs. Compared to Singapore’s more centralized and efficient legal system, India’s legislative procedure is slower since it involves both the national and state legislatures. Singapore is renowned for its rigorous criminal justice system, which has severe punishments for offenses including drug trafficking and corruption, as well as its strong enforcement of the law. In contrast, India’s legal system prioritizes the preservation of individual rights but confronts obstacles including backlogged courts and a lengthier reform process.

Conclusion

Singapore’s legal system is a combination of the colonial roots of Singapore and the modern reforms keeping in mind the principles of adaptability to its cultural, social, and economic needs. The structure is marked by a well organized judiciary, from the Supreme Court to specialized tribunals, ensuring efficient justice delivery. Understanding the nuances of the Singaporean legal system is crucial not only for legal professionals but also for anyone seeking to engage with Singapore on a global stage.

If the intricacies of the Singaporean legal system have sparked your interest in pursuing legal studies there, you might be wondering how to navigate the vast landscape of options and choose the right jurisdiction for your aspirations. This is where Project LL.M. comes in. We specialize in providing in depth insights into various legal systems, empowering you to make informed decisions about your legal education journey.